DAMASCUS, Syria — The bedroom featured soft recessed lighting illuminating elegant cornicing and the dimpled headboard of the bed below. The mattress, though, was resting on the coffee table in the middle of the room.

Guarded by bulletproof doors several inches thick, this was the master bedroom in one of the palaces owned by Syria’s former president, Bashar al-Assad, and his wife, Asma, until they were forced to flee to Russia this week with their adult children.

Assad was swept from power by a lightning-quick rebel offensive after a 13-year civil war and six decades of his family’s autocratic rule, and the opulent trappings of a regime that inflicted terror and poverty on Syria’s people are now clear for all to see.

When NBC News gained access to the squat, modernist palace perched in the mountains above the capital, Damascus, on Wednesday, it was relatively calm, despite the appearance of having been robbed. Fighters from the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham militant group, which led the rebel overthrow, stood guard, checking cars in a bid to put a stop to any more thefts from the building that was Assad’s main residence until he was forced into exile.

Inside, doors opened with a hefty sweep into a cavernous, marble-lined dining room with a table that can comfortably seat three on each end. The chandeliers above appeared to be the finest crystal.

It also appeared that no expense had been spared at one of Assad’s guest palaces nearby. While one room had been torched and its chandeliers were covered in ash, some of the others looked like they might have been robbed, although art remained on the walls and the mother-of-pearl inlay was still in the doors.

New carpets on renovated staircases were still under the plastic they came with, as were expensive-looking pieces of furniture, giving the impression that Assad had been planning to be in power for a long time.

Back in his own palace, a room was set up as a doctor’s surgery and another for a barber — complete with the chrome and leather presidential barber’s chair.

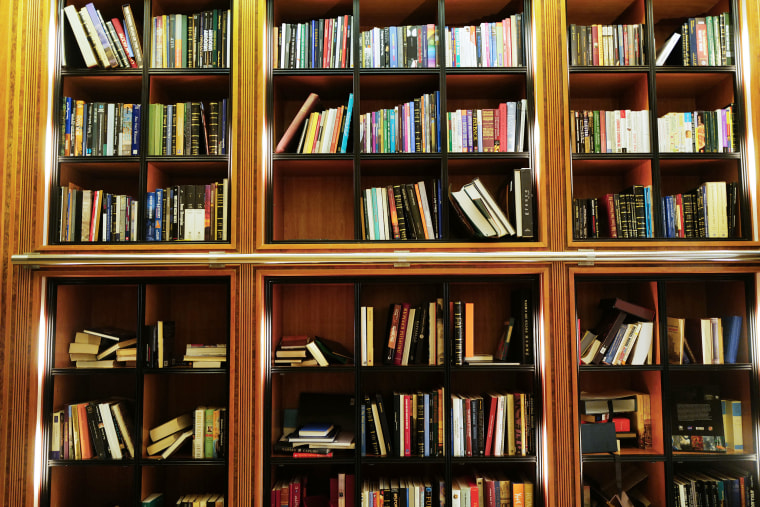

Elsewhere, there was an expansive library large enough to warrant a rolling ladder. Books including storybooks for toddlers and guides to Uruguay, Croatia and Sudan still lined its wood-paneled walls. A copy of Michael Moore’s “Dude, Where’s My Country?” and one of anthropologist Sue Black’s “All That Remains” — a memoir recounting her experiences working in war and disaster zones, had also apparently been on Assad’s reading list.